About me

Curious and creative professional, passionate about communicating complex topics in a way that is simple, elegant and engaging. Interested layout, web and graphic design, motion graphics and writing.

Graphic Design

For Print

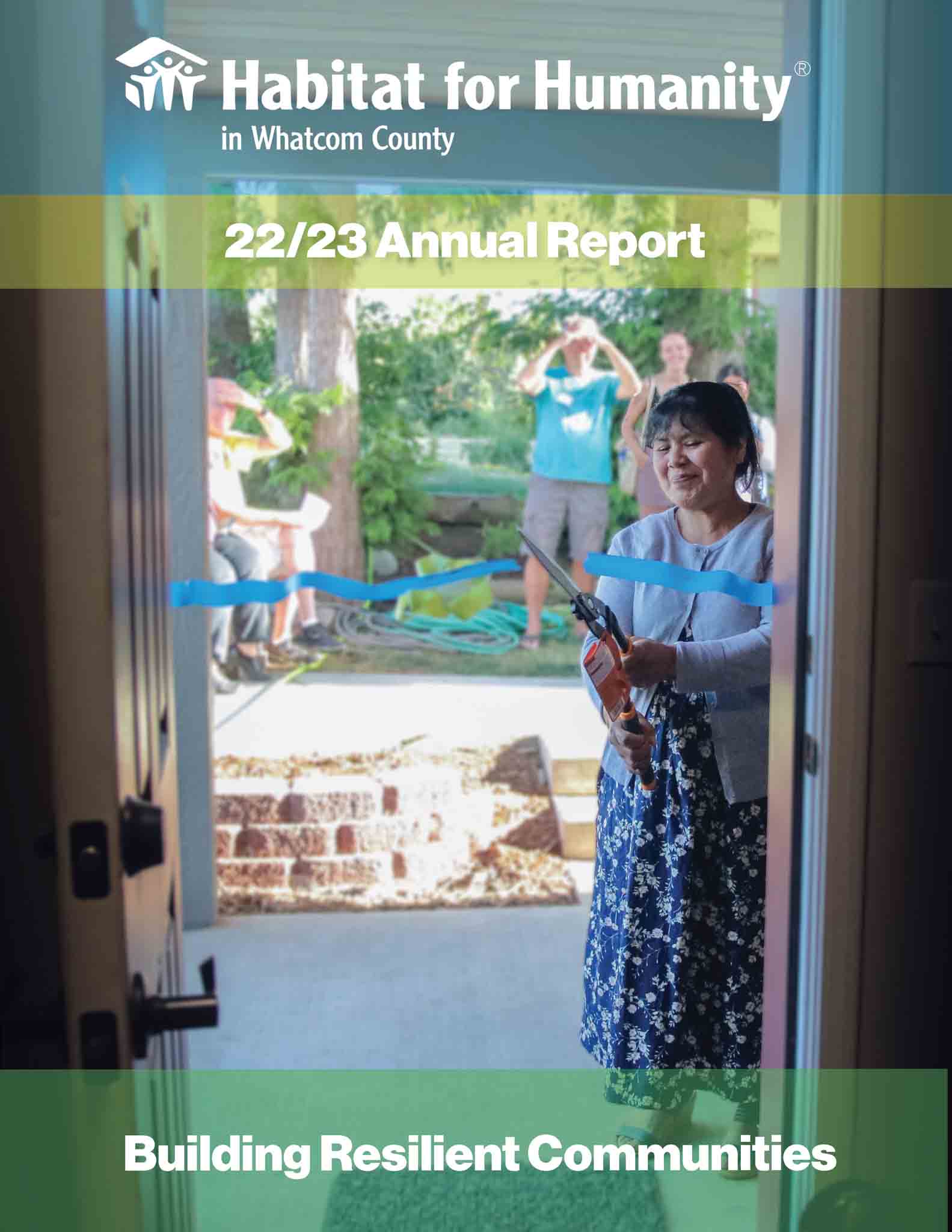

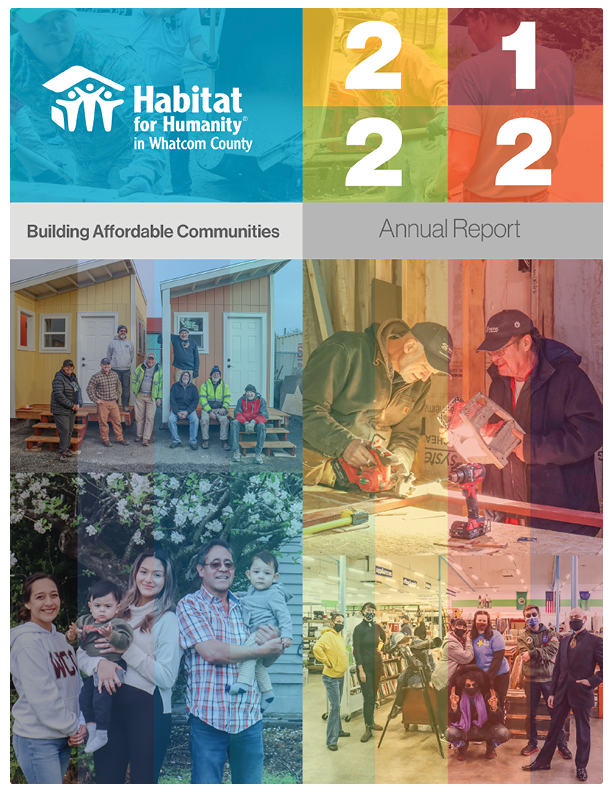

Annual Report

Annual Report

Annual Report

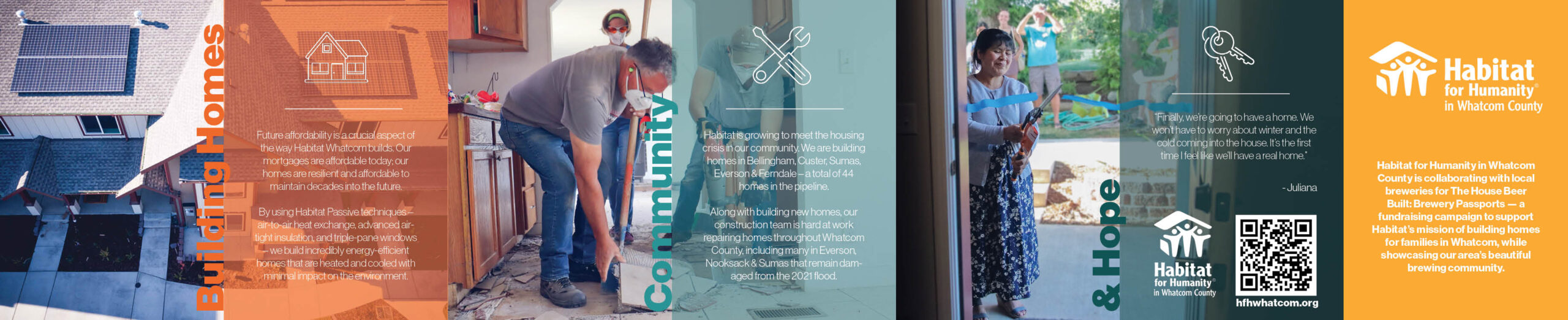

Fundraising Brochure

For Web

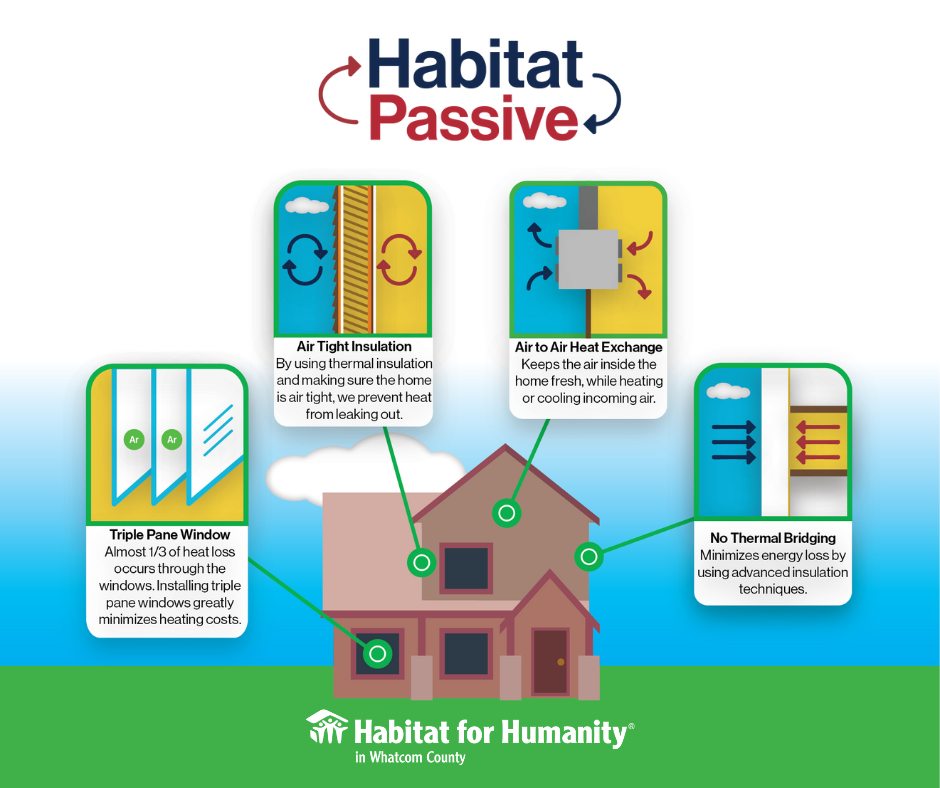

Habitat Passive Illustration. Created with Adobe Illustrator.

Event Invite for Social Media using Canva.

Event Logo — Unlock the door to homeownership — using Adobe Illustrator.

Writing

Funding Cuts for Albuquerque's Public Services

Mary, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, lives in a subsidized apartment complex off of Central Avenue with her daughter. She doesn’t feel safe in the area. There’s a constant presence of police officers circling her neighborhood or walking the hallways of her building. All in all, it seems to be a position she isn’t used to, but she is grateful for the cheap rent and the forgiving due dates.

Not long ago, her life was thrown into chaos. While dealing with a physically abusive marriage, she was diagnosed with lupus. She managed to escape to New Mexico, and has depended on

public and non-profit assistance since then to help her deal with her illness. She spends 90% of her time going to doctors, she explained, “I have five of them,” and while pointing to different parts of her body she listed them: her heart, kidney, brain, lungs, and a rheumatologist for her joints. For this she depends on Medicaid.

Lupus is an auto-immune disease that attacks the kidneys, and causes hypertension, flaring and rashes. “This summer has been good for me,” she says, but on bad seasons she can be constrained to her bed for weeks at a time, so she depends on meal deliveries to help her get by. There are two meal programs in Albuquerque. Senior Meals is run by the city, and provides one type of meal and only to seniors above 60. The future of this already underfunded program has become uncertain after the White House budget, released in March, threatened to cut funding for the Department of Health and Human Services. It is still unclear whether Congress will follow through with this proposal.

Another proposed budget cut from the Trump administration is to the Community Development Block Grant, which is part of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, now run by Doctor Ben Carson. In many states, though not in New Mexico, the program Meals on Wheels is partially funded by this grant. This issue was brought to the spotlight in March, when Trump’s budget director, Mick Mulvaney said, when asked about cuts to Meals on Wheels, “We can’t spend money on programs just because they sound good.”

Meals on Wheels of Albuquerque is the only other meal delivery program in the area, and has chosen to operate completely without federal funding, partly in order to avoid the impact of such funding cuts on the federal level. But this decision is not without great sacrifice. Meals on wheels currently has a long waiting list, filled with people in various circumstances, that, for one reason or another, are unable to apply for the Senior Meals program; reasons which could include age or dietary restraints.

Furthermore, financial independence from the federal government does not fully relieve them of the impact, since they are left to care for the clients the city can no longer afford. “A cut won’t

affect us directly,” said Shauna Frost, the Executive Director of Meals on Wheels of Albuquerque, “but the city could potentially see some funding cuts.” If this were to occur, she explained, the city would most likely redirect funding to keep the program alive, but, “if that doesn’t happen, and they are forced to turn people away from their program, we could see an influx of seniors who are needing our services that we do not have the funding to support.”

Not only as a director, but as a resource to various services that people like Mary need, Frost is in the position to see the full impact of these cuts. Mary is fortunate to have been on the Meals on Wheels waitlist for only three months. That program was her only option, since, at 52, she’s too young for the city’s meal program. “I can say from my personal experience that this program definitely works,” she explained, “without it I think a lot of us would starve.” But the future remains uncertain for her medical and housing needs. So far this year, every program she depends on has been put under threat, either by Congress or by the Trump administration, and it is likely the full repercussions of their cuts won’t be known until it’s too late.

Introduction to Habitat Whatcom

The following was published on December 2021 in Whatcom Watch — a community newspaper that covers local environmental issues.

Habitat for Humanity was founded in 1976 based on a model of building called “Partnership Housing.” This model was developed by Clarence Jordan, a biblical scholar living just outside of Americus, Georgia, and it is still how Habitat operates today. Volunteers partner with families in need of adequate shelter to build a home. The home is sold to the family for the price of the materials used with a 0 percent mortgage. Those mortgage payments are then used to fund future Habitat homes.

Today, Habitat operates in 70 countries, and is the largest nonprofit builder in the world. What was true in a rural community in Georgia half a century ago, is true in Haiti, Kenya, Cambodia, and everywhere else — housing is a human right, and everyone, regardless of race, faith, gender, sexual orientation, or nationality, deserves a safe, decent, affordable place to call home.

In Whatcom County

Habitat for Humanity in Whatcom County was born in 1988, as a locally run and operated affiliate of Habitat for Humanity International. Since then, we have built 52 homes, and restored 12. The families in our homebuyer program are Whatcom County residents living in substandard conditions, which we define as unsafe, transitional, overcrowded, or where 30 percent or more of their income is spent on rent (today, this latter requirement seems to apply to everyone).

For the first 25 years, our Whatcom Habitat built homes the same way Habitat for Humanity always had: simple, decent, single-family homes. We built roughly a home a year on donated or inexpensive land. Over the last few years, however, three growing, and distressing challenges have changed the way we think about building shelter.

Habitat Passive Homes

Housing is a significant contributor to carbon pollution. Not only because of the techniques and materials used during construction, but the way a home is built will decide how much energy it will consume for decades into the future. That’s why we borrowed techniques from the Passive House movement, adapted it to our own needs, and began building what we call Habitat Passive homes. There are typically four principles to our type of home design: minimized thermal bridging, triple pane windows, airtight insulation, and the use of heat recovery ventilation.

The result is a home that is incredibly well insulated, and can be warmed by the wattage it takes to power a hair dryer even on the coldest winter days. In 2013, we built our first Habitat Passive home for the Huentes family in Birch Bay.

Energy efficiency is not only inherently favorable, it also means permanent affordability for our families. Though the cost of building is higher, that cost is justified if the product is a home that produces more energy than it consumes, with a mortgage that is still cheaper than renting a two-bedroom apartment in Bellingham.

Telegraph Townhome Project

Along with sustainability, the drastic rise in land prices also guided us into building more than just single-family homes. The Telegraph Townhome Project came out of our need to face these two enormous challenges at once. We could design a higher density community, build between four and eight more homes a year, and make them as energy efficient as possible. Furthermore, we felt that the affordability of our homes should benefit more than our partner families. With the meteoric rise in land prices in Whatcom County, we as a community need to be creating permanent affordability wherever we can, if there is any hope of preserving housing opportunities for low- to middle-income families in the future.

With permanent affordability in mind, we partnered with the Kulshan Community Land Trust for the Telegraph Townhome Project. By keeping the land under the Telegraph project in a community land trust, those homes will remain affordable to whoever comes next. Every home in the Telegraph Townhome Community will be built using Habitat Passive design, and, thanks to a grant awarded by Puget Sound Energy, we were able to partner with Western Solar to provide solar power to the first 12 units. We were also able to obtain enough panels to provide community power to the buildings through our partnership with Ecotech Solar.

By facing these challenges head-on, we can do more than build houses — we can build communities. This fall, we made an offer on a 3.46 acre lot in Everson, where we will be building commercial spaces, along with affordable townhomes. Having shops and businesses could make our Net-Zero ready, permanently affordable neighborhood, much less reliant on transportation. Our homebuyers will not only have businesses they can walk to, but job opportunities as well.

From Homelessness to Homeownership

When home prices rise beyond reach, so does rent, and the entire housing continuum is stressed. Subsidized housing is quickly taken up, and organizations like ours are overwhelmed. Homelessness is the clearest consequence of this imbalance.

The traditional Habitat for Humanity model has never been well-suited for the chronically homeless. The ability to make mortgage payments, even at 0 percent, requires a level of stability that is difficult to achieve when you don’t start every day with stable shelter. But, we know that the journey from homelessness to homeownership is possible. Some of our homebuyers have made it.

We also know that to make that happen, we need to provide housing first. This past year, we partnered with the nonprofit, HomesNow, and the city of Bellingham to build two tiny homes that will be transported to Unity Village, and serve as transitional housing. Building these small but durable shelters is a great way for Habitat to engage more volunteers and develop ways to build stepping stones along the housing continuum, all the way to homeownership.

Our Need

Though our methods continue to evolve based on the needs of our community, the way we work has not changed. All that we do, and how quickly we can do it, depends on volunteers. As the need for affordable housing becomes more dire, and as we expand into bigger, multifamily housing projects, our success will rely greatly on those who are willing to partner with our homebuyer families and help them build a place they can call home.

If you have never volunteered with us before, we hope you will consider it. No experience is necessary, and we provide all of the tools needed. Our build sites are open from 9 to 4 p.m., from Wednesday through Saturday. Please email volunteer@hfhwhatcom.org with any questions. We also have volunteer opportunities at events, the Habitat office, and our Habitat Store.

The Habitat Store

Donating or shopping at the Habitat Store is probably the easiest way to help bring affordable housing to Whatcom County. Located near downtown Bellingham, the Habitat Store accepts new and gently used items, such as furniture, appliances, construction supplies, clothes, hardware, and so much more. Our store is our most critical source of funding, and all of the proceeds go towards our efforts here in Whatcom. You can donate your new or gently used items at our donation dock, or by scheduling a free pickup online.

Visit us at hfhwhatcom.org to learn more about our current projects, the families we serve, and how you can get involved today in helping Whatcom families build strength, stability, and self-reliance through shelter.

Flood Concerns at Mateo Meadows

A block south from the Everson Market sits a 3.6 acre flat field, with nothing on it but green grass, a yellow barn and a gravel driveway leading to it. Habitat for Humanity in Whatcom County purchased that property last year with plans to build a community there, consisting 30 townhomes, 7,000 square feet of commercial space, and at least 8 apartments – an investment of at least 12 million, all a stone’s throw from downtown Everson. It will be called Mateo Meadows and it will be a mixed-income, mixed-use community that Habitat will put into a land trust for permanent affordability.

Construction has not yet begun, but for Habitat, this project is a couple years in the making. The development needed support from the Everson City Council who approved a conditional use requirement, allowing for both commercial and residential buildings. Habitat received help from our county executive, as well as the Whatcom County Council; they approved roughly $450,000 in ARPA funds for land acquisition. A hydrology report was also ordered to gauge the impact in the surrounding area, given that almost all of Everson and Nooksack are in a flood zone. Habitat is now waiting on permits, and hopes to break ground this summer.

For the city of Everson, this project has been 10 years in the making, with significant investments to develop Lincoln Street, as well as investments to revitalize the downtown area by improving roads and public facilities. The city’s 2016 comprehensive plan details its desire to create a denser, more walkable downtown (leading to economic growth, while minimizing the burden on the city’s infrastructure), the need for all housing types, as well as the desire to attract new businesses, all with the goal of developing Everson simply as a “bedroom community” for the rest of Whatcom. Along with adding commercial space, Mateo Meadows would put well over 100 people (with an affordable mortgage) within walking distance of downtown.

Meanwhile, the city’s need for affordable housing continues to grow. Everson Meadows, lost in the 2021 flood, meant the loss of 24 affordable housing units, and the displacement of families – including 50 school-aged children – who could not afford to be displaced. The timing is also crucial – affordable housing is one of the last steps on the road to recovery after a natural disaster, if it’s a part of it at all. Furthermore, the need is especially great in Everson, given that it is a historically cheaper place to live, compared to the rest of Whatcom. Being priced out of Everson, a low income family’s only option may be to leave our region.

It makes sense why response to this project has been incredibly supportive; the land is ready for development, the city and its infrastructure is ready for growth, the need for housing is tremendous.

But despite the support, there are some who are concerned. The site sits on the shallow edge of a flood plain, and was mostly (though not completely) submerged, roughly 6 inches, during the 2021 floods. Because of the flooding, some in the community have vocalized opposition to the project. Their worries are legitimate, and as far as we’ve heard, are a result of two central concerns.

The first, voiced by a few neighbors, is that the project will lead to greater flood damage to surrounding homes by displacing more flood water, since that displaced water has to go somewhere. The results of the hydrology report, executed by WATERSHED Science & Engineering, stated that, “Per City of Everson flood code, impacts in terms of predicted rise must remain below 0.1 feet. Maximum impact due to the assumed complete fill at the Lincoln Street Development is predicted to be only 0.002 feet, well below the allowable rise and even qualifying as “no-rise” per FEMA guidelines (rounding to 0.00 feet).”

Of course what we build impacts future floods, and we should limit the amount of development allowed in flood zones, but the report shows that if the Mateo Meadows community had been built prior to the November 2021 flood, the surrounding area would have fared no better or worse. Like dipping a leg into a swimming pool, the size of the floodplain, relative to the size of the buildings Habitat will build, will result in a rise in the water that is too negligible to measure. To this end, we feel confident in the math, and that Habitat’s project will not affect nearby homes in the event of another flood.

The second concern is that the homebuyers who will live in Mateo Meadows will eventually become victims of a future flood themselves, and, like the residents of Everson Meadows, will be similarly displaced. The first step for construction will be to raise the building sites one foot above the Base Flood Elevation (BFE). The slab foundations will raise the homes another foot, putting the homes two feet above the BFE. As above, the same comparison stands: If Mateo Meadows had been built before 2021, not only would the homes have been well above water – likely 2 feet – so too would the driveways.

Furthermore, as an extra resiliency precaution, Habitat plans on using attic space instead of crawl spaces to run ducts, power and venting, to limit damage in the event of a far more catastrophic flood. Preventing damage from future floods is a crucial part of long-term affordability for our homebuyers, and long-term affordability is inexorably tied to Habitat’s true goal: ending poverty forever for our partner families.

Along with doing our best to prepare for future floods, these homes will be built to the highest possible energy efficiency standards, using triple pane windows, air to air heat exchange, and a highly insulated envelope, and consequently be incredibly efficient to heat and cool. The first 12 units of the Telegraph Townhomes, a partnership project with Kulshan Community Land Trust, and the Whatcom Community Foundation, have also been equipped with both individual and community solar panels; we hope to increase solar energy at Mateo Meadows.

Beyond Mateo Meadows, Habitat is hoping to improve the resiliency of select Everson’s residences through our Neighborhood Revitalization Initiative. We’ve been working with the Whatcom Long Term Recovery Group to repair homes damaged by the 2021 flood, including a manufactured home community neighboring Mateo Meadows. Our volunteers are working side by side with volunteers from World Renew, and Christ the King. Through our Neighborhood Revitalization Initiative, we hope to grow our ability to affordably do both large and small repairs to existing homes.

The damage from floods of Nov 2021 has been an integral part of all the planning for this project, but Habitat believes the larger question is: how do we get our communities ready for a future with extreme weather? We’ve approached Mateo Meadows with the flood in mind, but also with the belief that Everson, like everywhere else, deserves affordable housing, and that our community shouldn’t stand by and watch the town starve for investment. We also believe that the effects of climate change – long talked about as a future problem for our grandkids – are with us now. To mitigate those effects, we need to build greener, stronger, more flood resilient homes, as we continue to repair and replace what was lost.

Photography

- People

- Travel